Throughout history, we’ve seen super weird engines in just about every kind of vehicle imaginable. But, one of the weirdest of them was created in a hurry during a time of war, when Chrysler assembled a ridiculous 30-cylinder engine to use in tanks during WWII.

And it sounds crazy, partially because it is and partially because it’s actually five separate Chrysler engines assembled in a radial format, all just to output a whopping 370hp from 20.5L of displacement. So, without further ado, let’s get into it.

Why Build a 30-Cylinder Engine?

Right off the bat, the question is why. What purpose does a ridiculously massive 30-cylinder engine have as compared say, an equally large six-cylinder gas engine, diesel engine, or anything else besides this ridiculous layout?

Well, to understand the why behind this engine, we need to first better understand the application for which this engine was designed: medium-duty tanks.

When the US entered WWII, there was a need for better medium-duty tank engines. And historically speaking, when the armed forces desperately need something, the US government often relies on US-based companies to come up with solutions and do so quickly.

With this in mind, it was Chrysler who ended up coming up with an idea for the medium-duty tank engines that were so desperately needed. And Chrysler’s idea was actually pretty simple: take some of their existing engines and bolt them together to make one bigger engine.

Not only was this simpler than designing a brand new tank engine, it allowed them to leverage existing products and stock, which theoretically meant faster turn-around times and quicker assembly, which was incredibly important for getting these tanks onto the battlefield.

More importantly, though, it allowed Chrysler to assemble much of the engine with the same tooling they used on their other engines.

Of course, the idea was simple, but the execution is where things get much more complicated. And I think it’s important to note here in the article, that medium-duty tanks, and specifically the Sherman M4, were vitally important to the US efforts in WWII, and you could very well argue that without those medium-duty tanks, the outcome could’ve been quite a bit different.

Bolting Six-Cylinder Engines Together

So now the question is, how do you use existing engines to create a singular 30-cylinder engine? And the answer is very simple: bolt them together and use gears to connect the crankshafts together for one central output shaft.

The engine the entire thing was based on was the Chrysler 4.1L flathead inline-six engine. Now, the flathead itself is a family of inline engines, including inline-4s, inline-6s, and inline-8s. All of which wasn’t particularly powerful, special, or interesting.

Also, for those who don’t already know, the “flathead” in the name of this engine simply refers to the intake and exhaust valves being in the block rather than in the cylinder head, which means the head is pretty close to just being a flat piece of iron.

And as you’d expect for an engine family that was born all the way back in 1924, power output was pretty bad at 68hp for the 1924 201 cubic inch model, but luckily the later 251 cubic inch model output a more respectable 120hp.

Still pretty bad considering the displacement of the engine, but at least better than it was.

It’s worth noting that the Chrysler flathead wasn’t just an automotive engine, but it was also an industrial engine. This engine had already proven itself as a decent engine for a variety of applications, so it made sense to start with it.

In order to get five of these 251 cubic inch inline-six engines together, Chrysler used one large cast-iron crankcase. The lower engines we’re mounted at 7.5 degrees above horizontal, the middle two are mounted at 27 degrees, and the top engine is mounted vertically.

For those of you familiar with radial engines that are often found in planes, you might notice that this looks roughly like half a radial engine, but the big thing to consider here is that radial engines have one central crankshaft, whereas the Chrysler A57 retains all five crankshafts of the original five six-cylinder engines.

To connect all the crankshafts, there are five drive gears connected to one main gear. Now, this obviously much different than having a flex plate or flywheel connected to the back of the crankshaft, but if it works, it works.

Fueling, Cooling, and Problems

Where things get very interesting is with cooling and fueling. After all, how on earth do you keep five engines cool when they’re all mounted right next to each other? That’s a huge amount of heat from the blocks, heads, exhaust manifolds, and so on.

According to online sources, the earliest engines actually used five water pumps, one for the engine and mounted in the OEM location, all driven by one serpentine belt, but this type of system had a lot of issues with load management between pumps, as the engines aren’t absolutely perfectly balanced with each other.

And with the load between each engine and water pump varying slightly, running one long serpentine belt for each water pump basically just ended in lots of shredded belts. So, as a solution to this problem, Chrysler switched to using one massive water pump to cool all five engines.

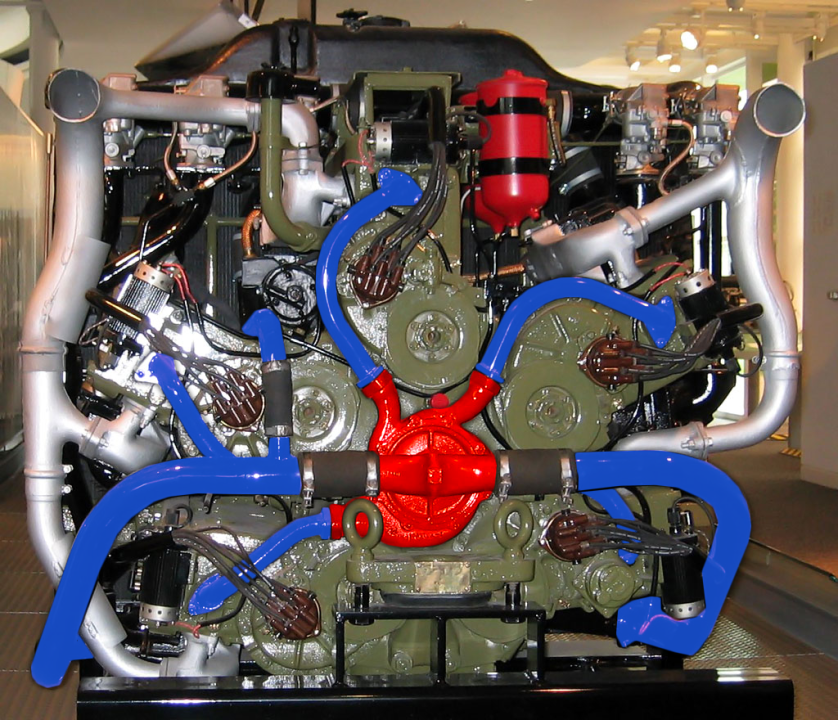

In this photo here, you can see how the singular central mounted water pump feeds each engine’s inlet, and you can also see the inlet and outlet for the radiator too. And do you notice anything weird about the water pump? There’s no belt!

You might be thinking the water pump is gear driven, and that’s also wrong. Instead, it uses one long accessory shaft from the central drive gear on the other side of the engine. Talk about a weird way to keep your engine cool.

To fuel the engine, Chrysler used five single-barrel carburetors, one for each engine. The way they originally fashioned each carb was simply on the intake manifold for each engine and then using one air cleaner for the entire thing.

But that system meant that each carburetor was a different length away from the air cleaner, which then led to fueling issues, as each bank was effectively getting different amounts of air.

To fix this, they moved each carburetor to a single plane above the engine and then used different-length pipes to connect each carburetor to the intake manifold. As to how this system didn’t cause fuel imbalances as compared to the original system, it’s not exactly clear, as both solutions we’re imperfect.

From what information is available online, they used flaps or metal veins in order to get the runners from the carburetor to the intake manifold even, or at least even enough, to balance out the airflow between engine banks.

For oiling, this engine uses two oil pumps: one scavenge pump to pump oil over to a remote reservoir and one standard oil pump to move oil throughout all five engines and keep everything lubricated.

Complicated yet Reliable

With all these things combined, the crazy intake system, central crankcase, shaft-driven water pump, and other super weird designs, there is no denying that this engine was very complicated. Some would even say that it looks like a German-designed engine, but the thing is, it worked.

The A57 worked so well that it’s known for still running just fine even with multiple banks of the engine broken and shut off from battle damage. With 20.5L of displacement and an incredibly high 6.2:1 compression ratio, power was impressively low at 445hp and 1,060lb-ft of torque for the most powerful models.

But, to be fair, that was enough power given the application. The unfortunate downside to this ridiculously large engine is its weight, coming in at over 5,200 lbs when fully assembled with radiator and all the running gear. Again though, for the application, this wasn’t the end of the world.

It’s not like Sherman was designing the M4 tank to be lightweight, like some sort of Miata tank or something. The tanks were already ridiculously heavy, so who cares if the engine weighs over 5,000 lbs.

It’s worth mentioning other hurdles that Chrysler had to clear in order to make this engine a truly viable solution. Problems like poor coolant flow from the water jackets being at an angle, overheating from radiator issues, piston ring failure, exhaust valve failure, and a lot more.

But, most of the problems we’re actually on the earlier models. In fact, the earlier models were so bad that the US Army supposedly wanted nothing to do with it.

With some changes, though, Chrysler was able to get the A57 to pass the 400-hour and 4000-mile endurance tests with only one failure in the four tank tests.

For comparison, no other power plant was able to achieve this, and as such, the A57 was deemed the most reliable medium-duty tank engine in 1944.

Summary

From April 1942 to September 1943, a whopping total of 9,965 Chrysler A57 engines were built. Roughly 7,500 of them were installed in production tanks, and the remainder were built as spare engines.

There are still some of them around today, but not a crazy amount, as civilians generally have a pretty hard time getting their hands on tanks, and as such, finding a running example of the A57 isn’t easy, but it’s also not impossible.

So, that’s the story of Chrysler’s ridiculous 30-cylinder tank engine. Be sure to check out the video below too!

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases made through links on this website.